Close window | View original article

RIAA's Tax Dollar Piracy

"Pirating" copyrighted works is not a criminal matter.

The Tennessean brings us this interesting news item:

State lawmakers in country music’s capital have passed a groundbreaking measure that would make it a crime to use a friend’s login — even with permission — to listen to songs or watch movies from services such as Netflix and Rhapsody... The legislation was aimed at hackers and thieves who sell passwords in bulk, but its sponsors acknowledge it could be employed against people who use a friend’s or relative’s subscription.

The topic of copyright protections and enforcement is one on which the Scragged community is deeply divided - so we'll set aside the underlying principles, or the law as it stands. What this particular new law is doing is even more interesting: far from defending a fundamental point of justice, it is providing unearned corporate welfare and special privileges, using tax dollars to provide private benefits which should be paid for by the parties involved.

Crimes and Punishment

What happens when Wal-Mart sees somebody shoplifting? They call the police. The police come and arrest the thief, who is presumably prosecuted, convicted, and fined or imprisoned. All this is paid for at public expense: your tax dollars pay the cop, the prosecutor, the judge, and the prison guard, then later on the parole officer.

Which is quite expensive to the public. In fact, after years of police complaints, Wal-Mart changed its policy to only have shoplifters arrested if they're making off with more than $25 in stolen goods; the rest they just glare at threateningly. Still, virtually every time anyone is prosecuted, the costs are overwhelmingly greater than the value of the merchandise involved.

Why do we, as a society, provide this subsidy to Wal-Mart? Because it's much better than the alternative.

In order to operate a functional business, you have to have some assurance of getting paid for your merchandise. If Wal-Mart couldn't count on the police and courts, it would have to do something else which we probably wouldn't like. Drug dealers, who cannot call the police for help when they're robbed, provide a cautionary example of how private enterprises defend themselves when they have to do it entirely on their own.

However, both businesses and individuals do have the right to defend themselves until the police get there, however long that might be. During the L.A. riots, several Korean store owners famously spent the night on the rooftops of their buildings armed with shotguns and flashlights. They defended their property until the National Guard showed up to do it for them the next day, at which point they peaceably packed up and went home.

The battle between "castle doctrine" advocates, who grant homeowners broad rights to defend against attacks on their property, and gun-control believers who expect cops to always arrive on time, is ongoing. As the bumper sticker puts it, "When seconds count, the police are only minutes away."

Regardless of cost, knowing that the police will show up fairly promptly cuts down on the violence and unpredictable mayhem in society. Certain categories of crime, particularly property and violent crimes, are so disruptive to the course of life and business that we need to present a publicly-funded united front against them.

Civil Action: Lawsuits, Not Crimes

There is another, completely different arena of the law: that of the civil suit. Just as a functioning economy requires public order and police to defend us against robbers and murders, it also needs courts to decide commercial disputes. Companies of any size employ teams of lawyers to review contracts, negotiate settlements, and if necessary, take violators to court.

Civil suits are entirely different from criminal trials. For one thing, they are almost entirely a matter of money. It's hard to put a price on not being murdered or having your home violated by burglars; it's quite straightforward to place a value on breaking contract terms or violating an agreement of some kind.

The time scale involved is also quite different. With theft and violent crimes, seconds count; with commercial disputes, the time involved matters only in the sense of the money it costs.

As a result, civil and contract disputes have not had the government involved in direct enforcement or prosecution. The injured party is expected to bring suit and provide his own lawyers, and the defendant provides his own lawyer too. Taxpayers contribute the judge and jury, but don't take sides while the case is under way.

Only once a decision has been handed down might the police get involved in enforcing it. For instance, when OJ Simpson was found civilly liable for the death of his ex-wife and her boyfriend Ronald Goldman, he was ordered to sell possessions to pay the judgement, including his Heisman Trophy. He sold the trophy to a collector and forked over the proceeds, but if he hadn't, the Goldmans would have asked the sheriff to take it from him and the court would have sold it on their behalf.

Not only does this approach save taxpayers money, it allows for more just decisions. The parties to the dispute have the opportunity to negotiate and may reach a fair settlement that works for both of them without needing to go through a full trial.

Criminal cases don't allow this, and shouldn't: Muslim sharia law permits accused murderers to negotiate with the families of their victims, which allows rich murderers to buy their way out of punishment for their crimes. That might have been nice for OJ, but the rest of us find the custom of "blood money" to be nauseating.

Have the government enforce commercial disputes the way it enforces criminal laws would put the police into every transaction or financial decision you make. We wrote about the terrible harm done by attempting to use criminal law to enforce MySpace's EULA in the sad case of a woman whose online harassment was said to have driven her daughter's class rival to suicide; this Tennessee law effectively does the same thing by criminalizing certain uses of computer log-ins.

Thieves in Places High and Low

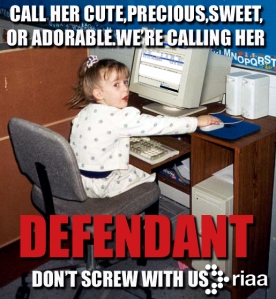

An argument can be made that "pirating" music or movies is theft and should be sanctioned. RIAA and the MPAA are famous for making life miserable for anyone who falls into their clutches, from grandmothers to kindergartners: poor Jammie Thomas was fined $2 million for sharing 24 songs.

She won't pay, of course; she hasn't got $2 million, and if she did, she'd have already paid it out in lawyer's fees. No more does the ordinary Wal-Mart shoplifter pay anything to Wal-Mart for the trouble they caused; Wal-Mart is lucky to get the shoplifted TV or whatever back in one piece after it's been used as evidence.

No matter how you cut it, unauthorized copying of media is not a criminal act and shouldn't be. It's a copyright violation; it's a breach of license agreement, if you believe that EULAs triggered when you open the package are enforceable. Nobody's privacy, property, or person have been invaded or removed; data copying is inherently a completely different class of act, just as we recognize that jaywalking, while a misdemeanor, is not at all the same thing as armed robbery or murder.

The only effect of this new law is to transfer the costs of enforcement from RIAA and the MPAA, where they rightfully belong, to the taxpayer, who if polls are anything to go by doesn't even think copyright violation is a crime at all. That's legalized theft and corporate welfare, no more and no less.

Time for a strange-bedfellows joint assault by smaller-government Tea Party types and Information-Wants-To-Be-Free lefties!