Close window | View original article

Why Uncle Sam Can't Google

It isn't worth fighting the bureaucrats.

The New York Times reports that the Air Force's Predator drones generated some 24 years' worth of video last year, even more video than all The Simpsons reruns put together.

While every second of the live video was watched as it was collected, there's been no effort to compare or index the video to see how a given area changes over time. The analysis problem will get worse when the newer drones arrive: there'll be more of them and the new ones have as many as ten cameras.

"If automation can provide a cue for our people that would make better use of their time, that would help us significantly," said Gen. Norton A. Schwartz, the Air Force's chief of staff.

Officials acknowledge that in many ways, the military is just catching up to features that have long been familiar to users of YouTube and Google. [emphasis added]

Americans are well aware that our intelligence agencies aren't the sharpest tools in the box when it comes to correlating information to prevent attacks. What we may not have realized is that the military has known since the early 1990's that unencrypted video from Predator drones could be intercepted by enemy forces. The Wall Street Journal reports:

Militants in Iraq have used $26 off-the-shelf software to intercept live video feeds from U.S. Predator drones, potentially providing them with information they need to evade or monitor U.S. military operations.

Senior defense and intelligence officials said Iranian-backed insurgents intercepted the video feeds by taking advantage of an unprotected communications link in some of the remotely flown planes' systems. Shiite fighters in Iraq used software programs such as SkyGrabber -- available for as little as $25.95 on the Internet -- to regularly capture drone video feeds, according to a person familiar with reports on the matter.

One of the most important aspects of combat intelligence is not only keeping the enemy from knowing what you know, but keeping the enemy from knowing what you can know. That's why it was such a setback for our military when the New York Times reported that we were tracking al Qaeda operatives by listening to their cell phone calls. They hadn't known we could do that, but once the Times told them, they cut back on their use of cell phones.

It's more than likely that the Times risked the life of the panty bomber's father who warned our embassy that his son had become radicalized - al Qaeda has shown its willingness to kill individuals as well as groups.

Even if this particular person who tired to give us information isn't killed, how many people are going to want to tell us anything if they think their names might be plastered all over the news?

|

|

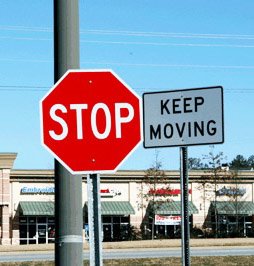

| Military Intelligence At Work |

|---|

Aid and Comfort to the Enemy

By leaving Predator video open to interception, our military has made it possible for our enemies to watch hours of our surveillance flights and understand how well our cameras operate. By watching what our people are able to see as our planes fly over their sites, the enemy can determine how well their camouflage works, for example, and they can get an idea where we're watching so they can go elsewhere.

One of the early concerns was that adding encryption would have added to the price of the Predator. That's true in the brain-dead world of military procurement where Congress' laws can require such complex overhead charges that a $2.98 hammer ended up costing the government more than $100.

Wired explains how other obstacles arise from the way the military handles encryption:

The naive reaction is to ridicule the military. Encryption is so easy that HDTVs do it -- just a software routine and you're done -- and the Pentagon has known about this flaw since Bosnia in the 1990s. But encrypting the data is the easiest part; key management is the hard part. Each UAV needs to share a key with the ground station. These keys have to be produced, guarded, transported, used and then destroyed. And the equipment, both the Predators and the ground terminals, needs to be classified and controlled, and all the users need security clearance.

Wired points out that military encryption is based on the old-fashioned notion that encryption requires keys which are distributed in advance, but that's way behind the times. Modern open source software offerings, which the military can use for free, include Open SSH:

OpenSSH encrypts all traffic (including passwords) to effectively eliminate eavesdropping, connection hijacking, and other attacks. Additionally, OpenSSH provides secure tunneling capabilities and several authentication methods, and supports all SSH protocol versions.

OpenSSH eliminates the key distribution problem because the source and target automatically negotiate a key which changes at various intervals during a session. The OpenSSH suite includes a data transfer protocol which encrypts files. Their user list is known to include companies like Cisco, Juniper, Apple, Red Hat, and Novell, but probably includes almost all router, switch or Unix-like operating system vendors.

This software is available for no money! It's been tested against hordes of hackers and crackers over the past decade and has turned out to be reliable. Using it would cost absolutely nothing!

Free Software Versus the Bureaucracy

So why don't the builders install OpenSSH on the Predator and be done with it?

The answer goes back to the fundamental nature of a bureaucracy. Public sector businesses prosper only as they can induce customers to come buy from them voluntarily. When a business doesn't attract enough customers, it goes broke unless it can persuade the government to bail it out as with GM.

A bureaucracy such as the DMV doesn't have to treat customers well. Nobody buys a driver's license from the DMV because the DMV folks treat them well, they go there because they have to under penalty of law.

Similarly, the encryption bureaucracy doesn't get business from government contractors because their software is so excellent or because they provide stellar service. The encryption bureaucrats get business because they are the only source of approved encryption software and contractors must deal with them. It wasn't installing the encryption software that would have run up the price of the Predator, it was dealing with the bureaucrats who approve the encryption software.

As procurement regulations now stand, the fact that OpenSSH works a lot better than the government's internal offerings matters not at all. There's no reason for the bureaucracy to approve OpenSSH and every reason not to - they'd lose their status as gatekeepers of encryption technology if any other software was permitted.

In the same way, we can't store intelligence data in a Google-like database where it could be searched easily because the keepers of the existing databases would lose power. We can't store intelligence video in a Youtube-like database for the same reason. So long as the intelligence operatives must deal with their internal computer departments and can't take their business elsewhere, there's no pressure for change or improvement.

In this case, the Predator contractor would rather expose our intelligence sources to eavesdropping than deal with the encryption bureaucracy, an understandable view on their part. All the while, our soldiers are at risk and our enemies prosper because we can't get our act together.

It's become evident that Mr. Obama has to start rolling heads in the intelligence agencies if he's to have any chance of getting them to share information. While he's at it, he ought to roll a few heads at our encryption agencies.